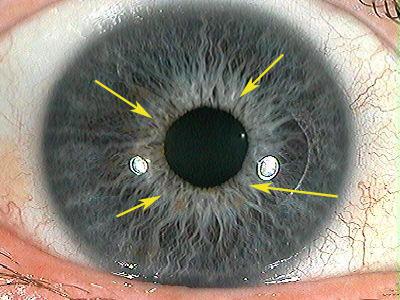

The Collarette (Autonomic Nerve Wreath)

The collarette is an anatomical structure derived from embryonic membranes and continues to mature until approximately three years of age. The zone between the external margin of the collarette and the pupillary border is of particular diagnostic interest, as it contains morphological features that have been correlated with systemic physiological states.

Experimental studies and clinical observations indicate that the structural integrity and morphology of the collarette are associated with:

Functional regulation of the autonomic nervous system

Gastrointestinal tract function

Endocrine regulation and dysregulation

Arterial circulation dynamics

The collarette is regarded as a vascular and neurovegetative analog of autonomic nervous system activity, reflecting cyclical processes of nutrient absorption and metabolic exchange between the intestinal tract and systemic circulation. Morphological features of the collarette have also been associated with the condition of the intestinal mucosa and autonomic tone.

A well-defined, circular collarette configuration is considered indicative of autonomic balance and suggests coordinated regulation between visceral and peripheral systems. Consequently, the collarette serves as a structural marker of gastrointestinal, autonomic, and overall nervous system function.

Morphological and Diagnostic Characteristics

The clarity, continuity, configuration, and contour of the collarette provide information regarding intestinal functional patterns and autonomic reactivity. The autonomic nerve wreath reflects adaptive responses to lifestyle factors, dietary influences, and psycho-emotional stressors. Clinically relevant features include the presence of crypts, stromal density variations, central heterochromia, and radial or contraction furrows.

An indistinct or obscured collarette is frequently associated with systemic toxicity and may reflect dysfermentative or dysbiotic processes. Collarette thickening has been interpreted as a possible indicator of increased intestinal permeability and chronic inflammatory involvement of adjacent lymphatic structures.

Variations in collarette expansion or constriction may also correlate with habitual physical or postural behaviors.

Key parameters used in collarette assessment include:

Relative dimensions of the pupillary and ciliary zones

Degree of prominence

Boundary clarity

Color characteristics

Geometric configuration

Developmental and Functional Considerations

In neonates, the collarette is minimally differentiated and typically becomes fully discernible between three and five years of age. Initially, it appears as a continuous or segmented elevated ring overlying the deeper mesodermal layer, formed by prominent trabecular structures.

The autonomic nerve wreath is a dynamic structure capable of expansion and contraction in response to changes in pupil size and pupillary belt width. For this reason, biomicroscopic examination under conditions of pupillary constriction and bright illumination is optimal for assessment. This region is diagnostically important, as collarette morphology reflects integrated visceral system activity and provides a reference point for targeted functional evaluation. The height and width of the collarette have been used to assess sympathetic autonomic tone.

A regular, near-circular collarette results from balanced interaction between the iris sphincter and dilator muscles. The sphincter pupillae consists of approximately 70–80 discrete segments, while the dilator muscle contains a comparable number of distributed segments. Normal collarette morphology depends on coordinated activity between these muscular elements under parasympathetic and sympathetic regulation.

Sustained visceral dysfunction and persistent pathological viscero-iridal signaling may disrupt autonomic balance, leading to alterations in pigment metabolism and structural deformation of the collarette.

Color and Structural Abnormalities

Under physiological conditions, the color of the collarette corresponds closely to that of the surrounding iris. Any localized or generalized change in color intensity is considered pathological.

Structural abnormalities of the collarette have been associated with dysfunction in corresponding organ systems. Among these, collarette rupture represents a severe finding and may indicate irreversible autonomic impairment or hypofunction of related organs. For example, rupture in the superior collarette region has been associated with neurological disturbances involving the cervical spinal segments.

Disease-Associated Patterns

Clinical and experimental studies, including those conducted in Russian medical research centers, have identified associations between specific collarette alterations and certain disease states. Structural disorganization of the iris stroma within cerebral projection zones, combined with localized collarette protrusions, has been reported in patients with schizophrenia. Some individuals exhibit bilateral protrusions without rupture (“horns” phenomenon), while others demonstrate protrusions accompanied by disruption of collarette continuity.

Localized outward deformation of the collarette has been associated with pathology in anatomically corresponding organs. For example, lateral collarette protrusions in both irises have been documented in patients with cardiac conditions such as post-infarction cardiosclerosis, rheumatic valvular disease, and left ventricular hypertrophy. Studies have reported that protrusions in the cardiac projection zone of the left iris occur approximately three times more frequently than in the right. The degree of deformation has been correlated with myocardial remodeling severity: mild deformation with compensated hypertrophy, moderate deformation with early dilation, and pronounced deformation with advanced dilation. Rare rupture in this region may suggest aneurysmal changes.

Ptosis of abdominal organs produces characteristic collarette changes. Mild transverse colon ptosis may be reflected as subtle flattening in the superior collarette region, while pronounced ptosis with multivisceral prolapse is associated with marked flattening of both superior and inferior collarette zones. Inferior flattening must be differentiated from changes in the 5:00–7:00 sector, which are more closely associated with duodenal ulcer disease or hereditary predisposition to gastroduodenitis.

Additional associations include collarette alterations in bronchopulmonary projection zones in bronchial asthma, cerebral and pelvic projection zones in lower-extremity atherosclerosis, localized inward deformation corresponding to colonic strictures, and small focal deformations associated with colonic diverticula, particularly in diverticulosis.

Functional Reactivity

Recent investigations emphasize that, beyond static structural features, the dynamic response of the collarette to physiological and external stimuli is of diagnostic relevance. The collarette typically mirrors pupillary constriction and dilation movements. In individuals with stable autonomic regulation, these responses are synchronous and symmetrical between both eyes.

Altered central nervous system excitability may disrupt this synchrony. While certain organic brain lesions may preserve bilateral symmetry, psycho-emotional disturbances often impair both synchrony and consensuality of responses.

Analysis of these dynamic reactions—closely linked to higher cortical regulation and reflex mechanisms—provides insight into excitation–inhibition balance, autonomic reactivity, and subcortical functional reserves.